In the aftermath of our late April fire we emptied the entire contents of our home. The excellent cleaning and restoration crew, First Service, for nearly 8 weeks photographed and bar coded every object we’d acquired, from the basement up. Unsalvageables were put in black plastic bags by the dumpster in our front yard for us to review and recover or toss. Anything that First Service deemed more expensive to restore than replace was trash. The rest was placed in brown cardboard boxes and taken to their facility for cleaning, after which items will go in white boxes labeled by room to be stored until we are ready for them.

In the aftermath of our late April fire we emptied the entire contents of our home. The excellent cleaning and restoration crew, First Service, for nearly 8 weeks photographed and bar coded every object we’d acquired, from the basement up. Unsalvageables were put in black plastic bags by the dumpster in our front yard for us to review and recover or toss. Anything that First Service deemed more expensive to restore than replace was trash. The rest was placed in brown cardboard boxes and taken to their facility for cleaning, after which items will go in white boxes labeled by room to be stored until we are ready for them.

These weeks of both facing the visceral proof of fire and the accounting of our lives through our belongings lent coming home a special kind of pain, with its burn and stale water odors, a film coating every book, decisions to be made: dump or salvage. Our son Kolter noticed how at first we were drawn to the house almost every day, as if not sure the fire had been real. “It’s like ripping off a bandaid,” he said, and every time it gets a little easier. Eventually he just stopped wanting to come, wound healing over. Why there is pleasure in it makes me wonder about how reaffirming our stuff seems to be: Mine. We had developed an attachment to what was ours, and now, to what happened to us, already claiming even this scary part of our story.

The task of sorting a single room can hold the intensity of a life event, something you would approach on a good day with a lot of courage and be done with in one fell swoop, ready to recover with a hot bath or a dirty martini. But what was left of our house persisted, oily residue on my hands, the whiff of the destroyed. I was good for about two hours at a stretch and often needed tough love friends to direct me to let go.

Deciding to damage out an item was easiest when for example photographs or camera equipment was fused, scorched, sodden, or shrouded with mold. More difficult were the merely contaminated cards and books and files, shoes and stuffed animals or building blocks.  We worked from the kitchen up, replaceable knives and fridge magnets to burned bedsheets; clothes; and toys; the gerbils’ cage and the life inside, gone; books upon books as we ascended the stairs through bedrooms to my attic/office, command central for my life of the mind, where I faced sadness blooming from ragged holes between floors and soot and more, from what might have been lost but wasn’t. I couldn’t see the full scope of damage for many visits, each one allowing for another loss to fill in what seemed like a gap in memory, a dissociation that initially served me well.

We worked from the kitchen up, replaceable knives and fridge magnets to burned bedsheets; clothes; and toys; the gerbils’ cage and the life inside, gone; books upon books as we ascended the stairs through bedrooms to my attic/office, command central for my life of the mind, where I faced sadness blooming from ragged holes between floors and soot and more, from what might have been lost but wasn’t. I couldn’t see the full scope of damage for many visits, each one allowing for another loss to fill in what seemed like a gap in memory, a dissociation that initially served me well.

Purging the contents of our home had been on my list. Friends of ours have been doing it since their youngest left for college. I’ve asked plaintively for help. My lament is that I cannot throw things away, that the act of opening a box releases memories in all five senses that envelop me, sometimes inspiring often paralyzing, awakening unarticulated emotions of longing, love, joy, loss, rage, sadness. Instead of making choices to unload, I tend to revel in the cocktail of ethers leading to places not useful in daily life, the sand dollar from a beach where I lay my head on my father’s chest and listened to his heart beating, holding on to that rhythm, his warmth, his allowing me to be so near.

It isn’t a secret that we had had trouble managing the stuff that seems to enter houses under cover of night and camp out on surfaces, somehow out of reach of racing time. I had uncannily said more than once aloud that I wish I could empty everything onto the lawn and return only that which I want. I’d lost control of stuff, our compact 1780s rooms cluttered with CDs, photos, mail, fossils, artwork, flyers, money, Magic cards, coupons, plastic tokens, and balls; shelves rimmed in dust.

The attic, the largest room in the house in which my husband, Steve, crafted my office, sheltered my computer, files, academic texts (gender, feminism, lit crit, fairy tale, dance, dystopia), poetry, childhood books, dvds … an intellectual record of my interests … and became the staging ground for the contents of two eaves the length of the house that kept from daily sight Christmas ornaments and wrapping; air conditioners; artwork and school papers; magazines documenting 9/11; Great Aunt Lilie’s recipes, lace, and newspapers, including the front page announcement of President Lincoln’s assassination; maps; brochures; picture frames; coasters; notes; collections of buttons, seashells, coins, and stamps; writing fro

The attic, the largest room in the house in which my husband, Steve, crafted my office, sheltered my computer, files, academic texts (gender, feminism, lit crit, fairy tale, dance, dystopia), poetry, childhood books, dvds … an intellectual record of my interests … and became the staging ground for the contents of two eaves the length of the house that kept from daily sight Christmas ornaments and wrapping; air conditioners; artwork and school papers; magazines documenting 9/11; Great Aunt Lilie’s recipes, lace, and newspapers, including the front page announcement of President Lincoln’s assassination; maps; brochures; picture frames; coasters; notes; collections of buttons, seashells, coins, and stamps; writing fro m the year I learned how through published essays; books; post cards; letters from boys and men, lovers and abusers, friends and family; my father’s files on my parents’ divorce. Some say to keep only that which brings joy but this seems a deception, an elision of truth that numbs my sense of having lived fully, and of having won.

m the year I learned how through published essays; books; post cards; letters from boys and men, lovers and abusers, friends and family; my father’s files on my parents’ divorce. Some say to keep only that which brings joy but this seems a deception, an elision of truth that numbs my sense of having lived fully, and of having won.

One eave burned for about 4 hours, torching tax returns and most of the auto mobile racing items that Steve had accumulated during a lifetime of professional racing, from caps and jackets to shirts, trophies, and articles, some of which he’d hoped to sell. There were photos and journals of his childhood kept by the family housekeeper for many years but Steve has held onto very little of nostalgic interest for its own sake: photos, car art, setup sheets, all proof of his reign at the Indy Motor Speedway, of his escape from Duluth.

mobile racing items that Steve had accumulated during a lifetime of professional racing, from caps and jackets to shirts, trophies, and articles, some of which he’d hoped to sell. There were photos and journals of his childhood kept by the family housekeeper for many years but Steve has held onto very little of nostalgic interest for its own sake: photos, car art, setup sheets, all proof of his reign at the Indy Motor Speedway, of his escape from Duluth.

Deeper into the eave, plastic bins melted and consumed their contents or protected them, such as a delicate coned paper ornament, a gift from my mother when I was in grade school. Lifting a box from spore-filled water in which soaked our sons’ baby clothes I recovered my great aunt Lilie’s silver, a motley mix of spoons and forks, bread knife and gravy ladles that fell into my hands as cardboard gave way. In the other eave were journals begun at age 7, pointe shoes, my mother’s dolls, playbills, blue books and workbooks, passport, plaster hand prints, and a father’s day card that describes my daddy as “gentel.” The attic in short housed a record of every phase of my and our children’s lives, clues to lives before ours, and proof of Steve’s intelligence, hard work, and passion, most of which burned or absorbed shadows of smoke and 45 minutes of fire hose water.

Lifting a box from spore-filled water in which soaked our sons’ baby clothes I recovered my great aunt Lilie’s silver, a motley mix of spoons and forks, bread knife and gravy ladles that fell into my hands as cardboard gave way. In the other eave were journals begun at age 7, pointe shoes, my mother’s dolls, playbills, blue books and workbooks, passport, plaster hand prints, and a father’s day card that describes my daddy as “gentel.” The attic in short housed a record of every phase of my and our children’s lives, clues to lives before ours, and proof of Steve’s intelligence, hard work, and passion, most of which burned or absorbed shadows of smoke and 45 minutes of fire hose water.

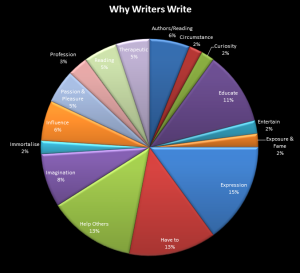

Everything in the eave that didn’t burn was carried downstairs to the living room, where I began an archeological dig through my life, memories reaching from inside each box like the flames that released them. Taken together from babyhood every item leads inevitably to the person I have become, the person who survived, who achieved her childhood goals of being a writer and a teacher, begging the question, If I am the living product, proof of energy created by interaction with these objects and the people who made them, why hold on?

Everything in the eave that didn’t burn was carried downstairs to the living room, where I began an archeological dig through my life, memories reaching from inside each box like the flames that released them. Taken together from babyhood every item leads inevitably to the person I have become, the person who survived, who achieved her childhood goals of being a writer and a teacher, begging the question, If I am the living product, proof of energy created by interaction with these objects and the people who made them, why hold on?

To look at the object is to remember. That’s all it is. And what’s the point of that other than it feels like coming home. It feels like living yet lies in intangible thoughts of the past. Maybe most of what we are is memory and we reanimate through these things, more equipped to move fluidly between worlds, the objects as conduits for the stories of our lives, a pathway in.

To look at the object is to remember. That’s all it is. And what’s the point of that other than it feels like coming home. It feels like living yet lies in intangible thoughts of the past. Maybe most of what we are is memory and we reanimate through these things, more equipped to move fluidly between worlds, the objects as conduits for the stories of our lives, a pathway in.

So when it comes to actually throwing away these keys to another world, I often cannot do it. I keep asking why, so engaged as I am in living, do I resist tossing these tangible parts of my past, anything that still releases through smell, texture, pattern a flurry of moving images always waiting in the recesses of my mind?

When my mother and stepfather sold the house I grew up in I packed away every precious thing as if to take each vitrified moment with me, wrapping them in paper towels, laying all to rest in harmony within sturdy boxes. I perhaps believed that one day, if kept safe, they might restore me to a better time, or that without them I was less tethered. It may have been my way of recording dreams, so that they would never be lost. Our objects seem to perform a service, to invite questions and observations that can reveal more than the evidence as it was carefully selected in increments over so much time.

The desire to archive the markers of my life was it seems to me now always present, as important as the objects themselves if not more so. I don’t know why. My brothers claimed it was conceit when they read my diaries, each page marked with my full name and date. Maybe it’s our culture of consumerism, the promise that stuff will fulfill and reveal ourselves to us, or was it the hope that I could later prove that I lived, that I was visible, that I was here? Kilroy. The girl who wrote about love all the time, championing the power of love in crayon on a leather suitcase, on cards to mom and dad, on buttons and T-shirts and plaques.

It has seemed that as long as all of these things are safely ensconced, if I could count and sort and name them I would experience wealth, sit on a treasure to counter childhood deprivation or brevity, the rationing of kindness, the changes that forced themselves upon me with an impartial eye. How does one spend one’s memories, one’s life, after it has been lived? How do we reap the benefits of a life observed and recorded so very well? Again, the dividend seems to be the reification of life once lived, the magic of having once been as seen through the eyes of one who is still becoming.

A friend packed away her childhood things, she remembers, for her future self. We keep the objects like a breadcrumb path to redemption, she says, that will lead us to our whole selves, explaining all. They are precious, possess a “luminous quality because we invest them with metaphorical significance, narrative significance. Writers, artists, are un-materialistic, but we invest great meaning in the material.” This is our richness, our legacy. So what meaning do I make of these things?

Am I piecing together and preserving a chronological narrative? If so, why, and for whom?

What happens if some of these items in the narrative are lost or reordered? Will a part of my story be lost?

And if a part of my story is lost, will a part of me be lost?

In this pbs article: http://www.pbs.org/program/objects-and-memory/ the word “continuity” jumped out: “objects that connect us to events provide us with a sense of our continuity.”

Proof of our being. Longevity, history. Legacy. I presumed to save these things for my children, imagined as daughters interested in claiming their pasts. As I had been the archivist of my family tree, hungry to own our tales, to find connection where detachment prevailed, so would they be interested in revelation. But the detritus in boxes means little if anything to my actual sons, who are so beautifully connected to the now, to shifts in light and flight of birds, to how we affect them from moment to moment: Will we be there or not? Will we see? Will we allow or deny, forgive or ignore?

There was a sense that if I just aligned all these things, set them out in order, dusted them off, that they would reveal something precious, something longed for and meaningful that I’ve needed nearly my whole life, something taken away. It feels like heaven will open up through the keys to this secret garden and I will be transformed, or the story will be other than I have remembered it. If I string them together in just the right way, meaning will speak through them, altered by the ephemeral nature of thought and feeling. I will have changed the material into the immaterial and thereby achieve something else to hold onto, weave a special magic by naming in sequence the unnamed.

I imagine that these old things will in time reveal more about me than I can decipher: the real me, the me who has silently harbored songs. From childhood on, I was quietly collecting things that would some day reveal more than I knew how to, convey more meaning than the objects themselves. I invested them with consciousness, with symbolism and messages about myself and how I understood the world. To jettison any piece of the puzzle is to lose hold of some greater being, some answer to the riddle I cannot or could not in childhood fathom without them.

My job then, in the someday future, is apparently to make sense of things in writing, or in telling, to translate the alchemy of becoming. The purpose is to complete the missing, to voice the unvoiced. The things are my silence beneath the events that led me to acquire them. They must be uncovered to release the lock on the saving, decrease the gap between my interior life—rich, dark, hyper stimulated, hungry, demanding, exhausting, impatient, judgmental, fearful, ecstatic—and the world outside myself, give voice to the memory as bridge to the actual, collapsing the distance between object and emotion. This alone would be magic, but there seems to be more available to us through our things, a synthesis that lies outside the rational ordering of our lives. More than reveal and narrate, things, once they have become immaterial, are free to reconstitute, transform.

Fire compromised my easy, seductive belief in revelation and meaning-making by chronological reportage, purified in the sense of obliterating neatly labeled compartments, forcing detachment. Or is it attachment, for objects also help me to remain attached, assist a poor memory like of toddlerhood where when the doll is taken away she ceases to exist. Memes, worn and familiar reminders of love and ambition, of learning and loss. I didn’t have to have a voice if these objects spoke for me, their swirl of perfume urging me to feel.

Fire disoriented by wiping away the linear, of meaning as understood by telling a narrative of the past. Fire urgently broke my story open, emptied the contents onto the lawn in no particular order. Photographs, baby clothes, crystal decanters ceased to remain in their coffins, fled, melted boundaries, reconfigured into spores, carbon, and air, new layers to line shelves. Is it possible then, that the inert objects I’ve so carefully saved will now change the outcome of the past, the trajectory of the future?

Cut the cord, the rope connecting the self and the chosen object. I lay out the leaves, I take pictures to save in their absence. I go through the motions of separating and attaching myself from and to each one. I revisit the time and place now reconfigured, connections between them newly acquired. Multiple stories unfold from a small collection of books now fuming. My mind races to see as much as I can before damaging out the leaves. Can new poetry arise from this?

I find that I am called upon to reframe all that was, make new sense of it, see it from alternate perspectives as each piece falls helter skelter into my hands, raked from the burn pile, torn and curled. Assembling fragments of x-rays and photos on the lawn I set them at new angles, a breast against the bones of my foot. My body is no longer known; it is separated and reformed as through eyes less reliant on physical time. Handling the material, I don’t know what I will find but the process is motion. Because we are alive here and now we make room for more, we organize. All is shifting contents, though, none of it stabilizing for long. I delve more deeply into compromised boxes, the writing faded: Once I’d thought that saving was preservation and now look, it’s only the affirmation that we don’t last. I’m sickened by the process, by not wanting to let go of that which is gone.

I find that I am called upon to reframe all that was, make new sense of it, see it from alternate perspectives as each piece falls helter skelter into my hands, raked from the burn pile, torn and curled. Assembling fragments of x-rays and photos on the lawn I set them at new angles, a breast against the bones of my foot. My body is no longer known; it is separated and reformed as through eyes less reliant on physical time. Handling the material, I don’t know what I will find but the process is motion. Because we are alive here and now we make room for more, we organize. All is shifting contents, though, none of it stabilizing for long. I delve more deeply into compromised boxes, the writing faded: Once I’d thought that saving was preservation and now look, it’s only the affirmation that we don’t last. I’m sickened by the process, by not wanting to let go of that which is gone.

Except for this: Living fully means allowing oneself to feel, and objects can help us feel. In a culture that values acquisition, that promotes speed and isolation, the act of remembering prompted by a ring, a sea shell, a card can bring us closer to ourselves and so to others, connecting our hearts and our minds. If we allow it we day dream, we learn more than we remember, know more than we can make sense of. We smell the first daffodil, hear lyrics long forgotten, and sing. If set free, memory can change the past as well as the now, will invite us to see more, to f eel our own hearts beating.

eel our own hearts beating.